Personality. Some people seem to have more (or stronger) ones than others, but how do we become who we are? Where or when does that start, and who is there to blame if I have a sh*t personality?

In developmental psychology, there is a hot debate between personality and temperament. Temperament is characterized by individual biological differences present at (or maybe even before) birth, which are independent of learning, values, and attitudes. In comparison, personality is more dynamic, although stable over long periods of time and takes experiences, cognition & emotions into account. Some psychologists believe that in early life, infants tend to lean towards the temperamental side, and later in adulthood, only a part of these temperamental traits form one's personality1–4. This makes sense, as in childhood you haven’t been overthrown by patriarchy or other socio-cultural constructs (yet), so you could say that you start off on a more temperamental note1. Ignorance is bliss, am I right ladies?

So, if children start off with temperament, which will later transform into personality, how does this develop? What traits fall under the personality category? In adults we define personality with the help of the Big Five, which is based on personality traits such as Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness. However, when it comes to kids, instead of the Big Five, they come with their own list of temperament traits: surgency/sociability, negative emotionality, persistence/control, and activity level2–6. These temperaments then translate into the Big Five with help of a list that merges temperament and personality traits for children: the “Little Six” (how cute is that?!)2,4. The Little Six list includes the five personality traits, together with activity level from the temperament. The addition of activity level is associated with emotion regulation (anger mostly), extraversion, and self-control. Here, low levels of activity will gravitate more towards low conscientiousness and agreeableness, and high levels are a sign of energy, enthusiasm, and positive (social) engagement in later years1,7. Interestingly, some researchers came up with the maturity hypothesis, which states that positive personality traits in adulthood grow from childhood to adulthood. For example, people may get more agreeable, more conscientious, and more emotionally stable as they age7. The opposite may be also true according to the disruption hypothesis, where big changes during the transition from childhood to adolescence can result in having trouble adjusting to new things. With finding it hard to adjust, you can imagine that one can get rather moody or snappy towards others, or “experience temporary dips in psychosocial maturity” as the experts say. In other words, changes can make you throw a tantrum again.

As children and youngsters develop so rapidly and have rather limited verbal abilities to really articulate what they mean or feel, it's quite complex to study their personality. However, there are several different ways of doing so, ranging from observational studies by researchers and clinicians to parent & teacher reports, stimulus-response tasks, and structured assessments such as age-appropriate tasks, games, or questionnaires for older children8. This could cover it pretty well, but it's still more difficult compared to studying personality in adults. This is because reports from especially parents could be biased. If you have to believe the majority of parents, their children are the greatest gift of the universe, which could possibly blur their objective view. Teachers may therefore probably have a more diversified view of a child, as they can often observe them together with other children in a classroom and have a more professional outlook and therefore objective point of view on their development.

Several psychologists and researchers have thought about human development in terms of cognition, learning, and social skills.

For example, the (in)famous Sigmund Freud proposed the psychodynamic theory in the 19th century9. This theory is based on the idea that personality is formed in the first years of life and that the interaction between the child and its parents or caregivers has a critical role in this. By interacting with our parents or caregivers, we learn how to manage our instincts and learn about socially acceptable behaviors. Here, Freud describes the three well-known parts of personality: the id, the ego, and the superego. The id is driven by basic needs and is based on pleasure and impulses, such as hunger, thirst, and sex drive. This is the part that we are born with, according to Freud, as humans are born as biological beings driven by instincts. In the first three years of life, a child starts to develop the superego. This part is driven by the interaction with our parents or caregivers, as mentioned earlier, since social interaction forms our morality, social thought, and acceptable behaviors. The id and superego are constantly having a conflict: do we go for instant gratification of our needs and give a big middle finger to the consequences, or do we stay in line and behave as is socially accepted? Here do we come to the ego, our reality and conscience, the rational balance between the id and superego. A good ego balance forms a ‘healthy’ personality. An imbalance towards their id might lead to narcissistic or impulsivity, whereas a super superego tends to be more anxious and controlling.

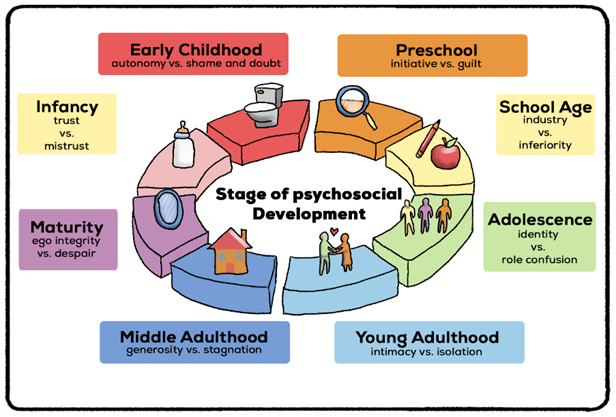

The German psychologist Erik Erikson theorized different stages of development based on crises or struggles (very relatable, I go through these stages multiple times a day)10. In total there are 8 stages, ranging from infancy to older adulthood. Starting from the beginning at infancy (0-1,5 years), there is a struggle between basic trust and mistrust. This is based on babies being entirely dependent on their parent(s) in terms of food, attention, and caring; this builds trust. By neglecting the baby’s needs, mistrust is being developed.

In the second stage of toddlerhood (1,5-3 years), the merry crisis is focused on autonomy versus shame/doubt. Here, autonomy is based on a toddler learning to do things on their own, where praising them stimulates self-belief and autonomy. By denying or discouraging them to learn independently, they may develop shame and become doubtful of their abilities.

Struggles in the preschool phase (3-5 years) are about initiative and guilt. This follows the previous stage pretty seamlessly, as a child wants to do things independently and begins to get an idea of aims and goals. Encouragement results in initiating new things and feeling more purposeful (might a quarter-/mid-life crisis be based on never getting out of this phase?! #healyourinnerchild).

Between the age of 6-11 years, children are in the (early) school phase, where the struggle between industry and inferiority arises. They become aware of their individuality and become keener on getting praise based on accomplishments in school and sports. Positive reinforcement creates a feeling of being competent and productive, while a lack of reinforcement results in a feeling of inferiority compared to others.

From the age of 12 to 18, we fall into the phase of adolescence, where we start to really think about who we are (again, it’s not a “phase”, mom!), and what we want to do in the future. Finding a place in the world “omg so many responsibilities and expectations, how do I handle this?” Welcome to puberty, or the first identity crisis. Spoiler alert: it will get better, but all the struggles mentioned above will persist. And don’t worry, Erikson notes that these struggle stages are not really black and white. They can overlap, and you don’t have to ‘complete’ a stage in order to progress to the next stage.

John Bowlby, and later Mary Ainsworth, were the pioneers in the 20th century when it comes to the attachment theory11,12. This theory describes the close relationship between the primary caregiver, usually the mother, and the child. This attachment of the child to the mother comes from the (never ending) need for safety, security, and protection that the mother can offer. As an infant, any mom can be your mom if they only give you consistent attention and social engagement. However, if your mom is not really mothering, your dad can also make up for that as a serious ‘secondary attachment figure’ (I will definitely use that term in arguments from now on). In the first six months of life, babies smile, babble and cry for the attention of their caregivers, and start to see the difference between familiar and strangers’ faces. Here, they tend to turn towards the familiar faces of their mommy and/or daddy. Around the first birthday, kids become clingier in order to be close to their caregivers. This explains the crying and following when a parent leaves and very happy smiles when a parent returns. These phenomenon associate with the term “secure attachment", as described by Ainsworth13. These children feel protected and safe and are able to get their sh*t together quickly once their caregiver returns. They also tend to be more confident, independent, and have good social and empathetic skills at a later age. Aside from secure attachment, there are three more categories that Ainsworth describes, which are less fun. The second category is “anxious-ambivalent attachment”, or “resistant attachment”. Children with this pattern will be more scared of new environments and new people, even when a parent is around. When the parent goes away, the child will get very stressed and will start crying or screaming, only recovering when the parent returns. As secure attachment is based on consistency, where this pattern is based on unpredictable responsiveness of the parent. Here, a child might get angry or feel helpless when a parent doesn't respond as needed. Research showed that this attachment pattern can be a result of abusive childhood experiences, where these experiences would later on cause problems in maintaining intimate relationships14. Another anxious pattern is “anxious-avoidant attachment”, where a child will avoid or ignore the caregiver and will show little emotion when they leave and return13. Ainsworth thought this indifference could be a mask to hide any distress. Moreover, she theorized that this pattern would refer to the lack of communication and trust from the parent, as their needs were not always met, and the child would believe that asking for comfort would be rejected. At last, the “disorganized/disoriented attachment” style was described by Mary Main in the 80's, where children show weird or unpredictable behavior when a parent leaves and comes back17. Sometimes the child is anxious when the parent leaves, while other times it seems indifferent about it. This disorganized behavior could be explained as the child is probably being flooded by fear. This attachment style has a bit of both the anxious-ambivalent and the anxious-avoidant attachment styles. This category was therefore aimed for children that don't really fit the classic categories, but it also blurs the perspective; some children would be categorized as securely attached, as their strange behavior doesn't show a lot of distress. Main found that most mothers of these children experienced major loss or trauma around time of birth and became very depressed as a result15.

Alongside Freud, Erikson, and Ainsworth, there are many more theories on childhood and personality development, such as Piaget and Bandura. It makes sense, as children can be these wonderful yet very weird and interesting little creatures. They learn so quickly, and are not even aware of it, as they are just getting more and more aware of life itself. Maybe we are fascinated by them because they are a mirror to our own life journey. We might think about the relationships we have with our parents, our friends, our (romantic) partner, and explain the dynamics based on your childhood. And maybe you even wonder what it would be like to see your own child growing up (if you haven’t already). So, if you can, choose your parents wisely, and otherwise it's never too late to become more “you”.

Author: Lotte Smit

References

1. Shiner, R. & Caspi, A. Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 44, 2–32 (2003).

2. Buss, A. H., Plomin, R. & Willerman, L. The inheritance of temperaments. J Pers 41, 513–524 (1973).

3. Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., Hershey, K. L. & Fisher, P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Development vol. 72 1394–1408 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00355 (2001).

4. Chess, S. & Thomas, A. Temperamental Individuality from Childhood to Adolescence. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 16, 218–226 (1977).

5. Hagekull, B. & Bohlin, G. Early temperament and attachment as predictors of the Five Factor Model of personality. Attach Hum Dev 5, 2–18 (2003).

6. De Pauw, S. S. W. & Mervielde, I. Temperament, personality and developmental psychopathology: A review based on the conceptual dimensions underlying childhood traits. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 41, 313–329 (2010).

7. Soto, C. J. The Little Six Personality Dimensions From Early Childhood to Early Adulthood: Mean-Level Age and Gender Differences in Parents’ Reports. J Pers 84, 409–422 (2016).

8. Markey, P. M., Markey, C. N. & Tinsley, B. J. Children’s Behavioral Manifestations of the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 30, 423–432 (2004).

9. Fonagy, P. & Target, M. The place of psychodynamic theory in developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 12, 407–425 (2000).

10. Orenstein, G. A. & Lewis, L. Eriksons Stages of Psychosocial Development. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, Models and Theories 179–184 (2022) doi:10.1002/9781119547143.ch31.

11. Vásquez, A. N. V. & Torres, M. P. P. Internal consistency and validity of the instrument Attachment between parents and newborn children. Enfermeria Global 19, 255–285 (2020).

12. Fox, M. K. & Borelli, J. L. Attachment Moderates the Association Between Mother and Child Depressive Symptoms. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research 20, 29 (2015).

13. Salter Ainsworth, M. D. & Bell, S. M. 5. Attachment, Exploration, and Separation: Illustrated by the Behavior of One-Year-Olds in a Strange Situation. The Life Cycle 57–71 (2019) doi:10.7312/STEI93738-006/HTML.

14. McCarthy, G. & Taylor, A. Avoidant/Ambivalent Attachment Style as a Mediator between Abusive Childhood Experiences and Adult Relationship Difficulties. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 40, 465–477 (1999).

15. Main, M. The ultimate causation of some infant attachment phenomena: further answers, further phenomena, and further questions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2, 640–643 (1979).