Imagine being a mental health patient in the 1940s. You are experiencing severe and visible symptoms of depression. You are introduced to a surgeon who, with a stick resembling an ice pick in his hand, claims that a 10-minute surgery will forever put your mind at ease. A scene that today may sound like the start of a horror movie was a reality in medical treatment in the mid-20th century.

Most of us have heard the term ‘lobotomy’ at least once in our lives, whether it was through a movie on TV or even a slightly unhinged “brainrot” post on Instagram. While only used as a slang word nowadays, this infamous term possesses a rich and especially controversial history that continues to entice psychologists and historians over a century later. The surgery, popular among neurosurgeons between the 1930s and 1950s, permanently changed various aspects of the cognition of tens of thousands of people throughout Europe and the United States. More often than not, this change resulted in detrimental consequences for the patient, thus leading to a shift in psychological treatment towards antipsychotic medication and ultimately to the fall of lobotomies.

From breakthrough to breakdown, forever etched into the dark history of psychology and neuroscience - the lobotomy.

The Rise of Lobotomies

Lobotomy was a form of neurosurgery in which the connection between the prefrontal cortex (brain area responsible for executive functioning such as higher-order thinking, decision-making and planning) and the rest of the brain is severed. The most common purpose and selling point of this procedure was that it supposedly alleviated symptoms of various psychopathologies, including schizophrenia, epilepsy and depression, among others, when symptoms are severe and extremely damaging to patients’ daily lives and functioning. While this “mind-silencing” procedure is considered brutal nowadays, in the mid-20th century, hundreds of physicians performed the lobotomy on tens of thousands of mental health patients.

Throughout history in psychological advancements, reports of the “first lobotomy” date back to as far as 1888, when six schizophrenia patients had undergone the procedure performed by a Swiss medical practitioner Gottlieb Burckhardt. Despite a general improvement in most patients’ condition, one patient passed away from the procedure and several had seizures and aphasia (inability to speak clearly) following the surgery, earning Burckhardt mass criticism from the psychological community and rendering his work “reckless”, ultimately disregarding it entirely. The first credible report of lobotomy was recorded in 1936 in the work of a Portuguese politician and neurologist Egas Moniz, who had also developed cerebral angiography, a method for brain blood visualization that may be used for diagnosing bleeding in the brain. For his first surgery, Moniz drilled two holes in his patient’s head and injected ethyl alcohol into the prefrontal cortex that severed the neural tracts thought to be responsible for the patient’s mental health problems. As the surgery managed to reduce (visible) symptoms of anxiety and paranoia, the surgery was deemed a success which sparked future attempts. For his contributions, Moniz went on to receive a nobel prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1949, allowing him to introduce the procedure to many more psychologists and laymen alike.

Surgery In Detail

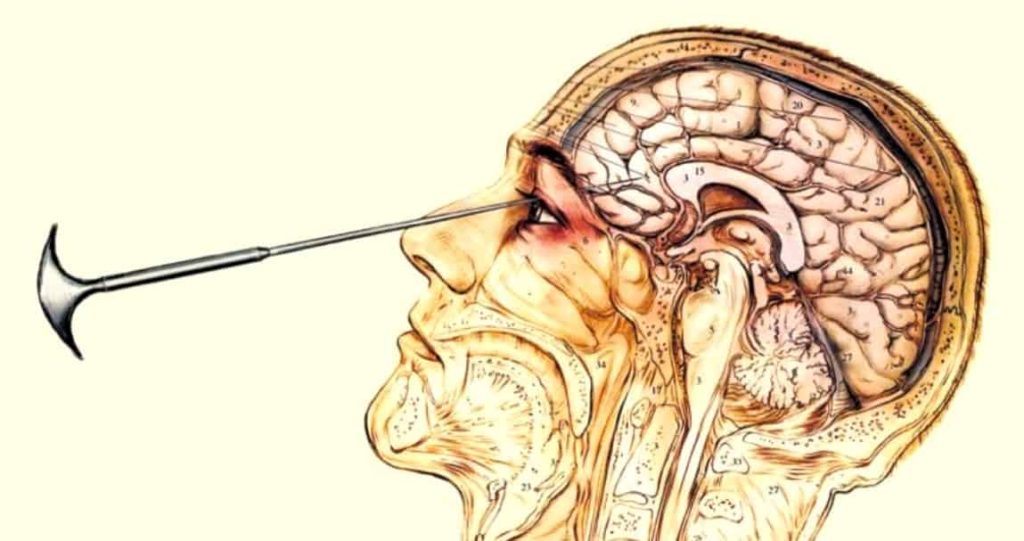

The purpose of a lobotomy, more specifically, was to sever the white matter of the brain which is composed of axons with myelin sheaths that connect gray matter areas (contain nerve cell bodies and dendrites) and allows for structural and functional connectivity between different brain regions. Generally, gray matter is where the information processing happens and it can easily be compared to a medieval castle as gray matter areas are the places where we say final “decisions” are made. White matter, as previously mentioned, are the connections between decision-making gray areas and can be compared to messengers which exchange information between nearby castles. By severing the white matter between two parts of the brain, their reciprocal communication would be lost, leading to impairments in performing certain functions related to the combined activation of those areas. For example, if you want to pick up a glass in front of you, the Supplementary Motor Area (SMA) is responsible for selecting which movement you should make (i.e. picking up the glass with your hand) and the Primary Motor Cortex (M1) would decide how to make that movement (i.e. extending your arm and grabbing the glass with your fingers.) If the connection between these two areas is severed, you may be able to decide that you need to pick up the glass with your hand, but you would not be able to determine how you are supposed to move your hand muscles to do this, which would ultimately make you unable to pick up the glass.

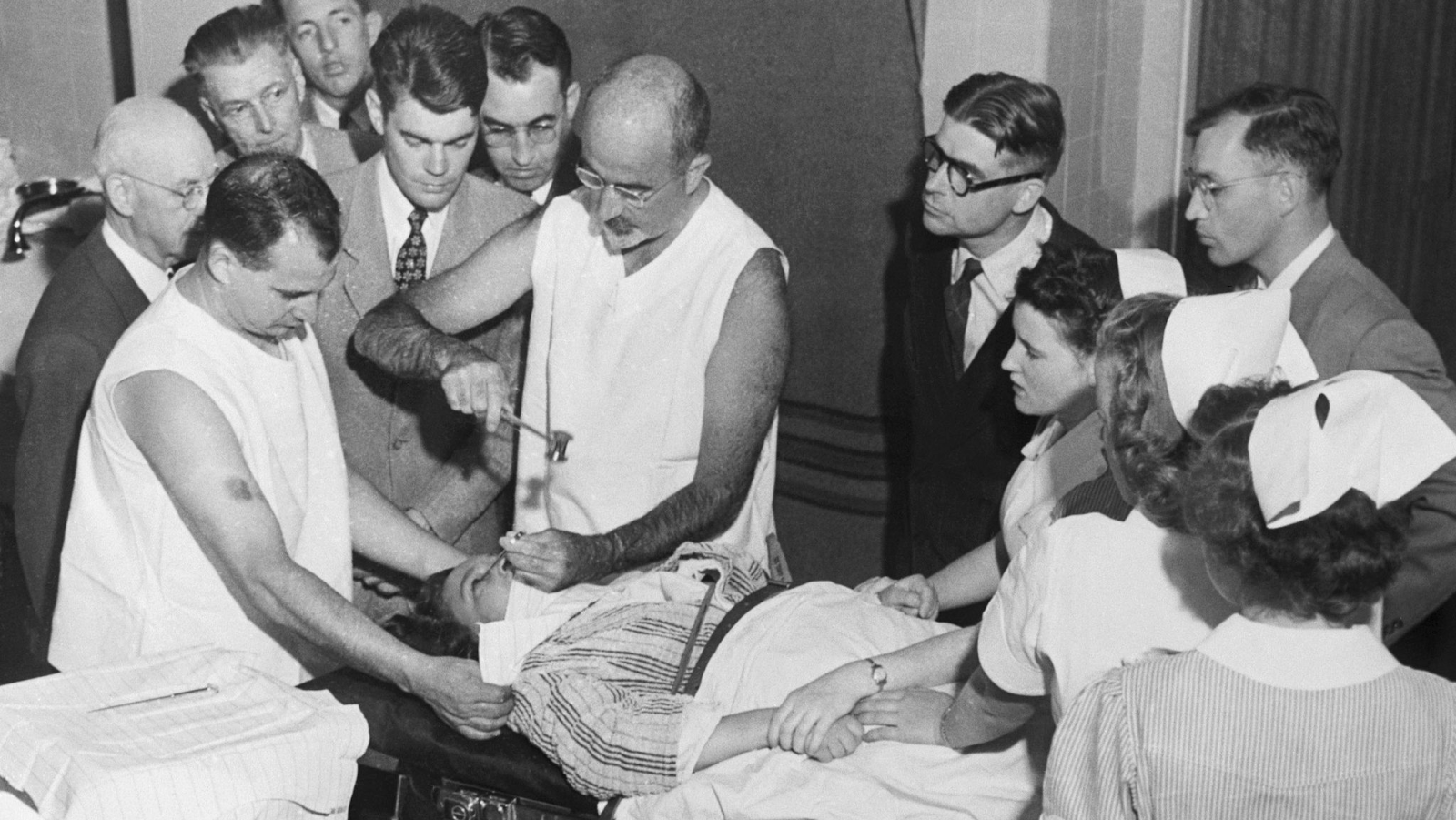

In order to destroy the white matter between the prefrontal cortex and the rest of the brain, neurosurgeons used a thin, stick-like device called a leucotome (also used by Moniz). The initial procedure involved drilling holes into the skull of the patient and then inserting the leucotome, which was used to remove parts of the white matter. Later, more advanced attempts at performing the surgery involved the use of a different, stronger leucotome named the orbitoclast. Coined in 1948 by Dr. Walter Jackson Freeman II, a neurologist and psychiatrist whose contributions popularized lobotomies, the orbitoclast was inserted through the top of a patient’s eye socket and hit gently with a hammer to break the layer of bone and enter the brain, after which the orbitoclast was twisted around to sever the white matter fibers.

(Source: Lobotomy to TMS: How Science Evolved To Treat Mental Health Ethically)

This advanced procedure, called the transorbital lobotomy, was performed through both eyes and lasted a total of approximately 10 minutes and was performed while the patient was under anaesthesia induced by electroconvulsive shock (using an electrical current to induce a seizure in the brain, thus inducing an unconscious state). Freeman reportedly considered only one third of his procedures to be a success (when patients were able to lead independent and productive lives), while another third of patients could return home but were unable to support themselves on their own following their lobotomies. The last third were failures which involved deaths, vegetative state, incapacitation or exhibiting a child-like state in which advanced thinking and complex expression was impossible.

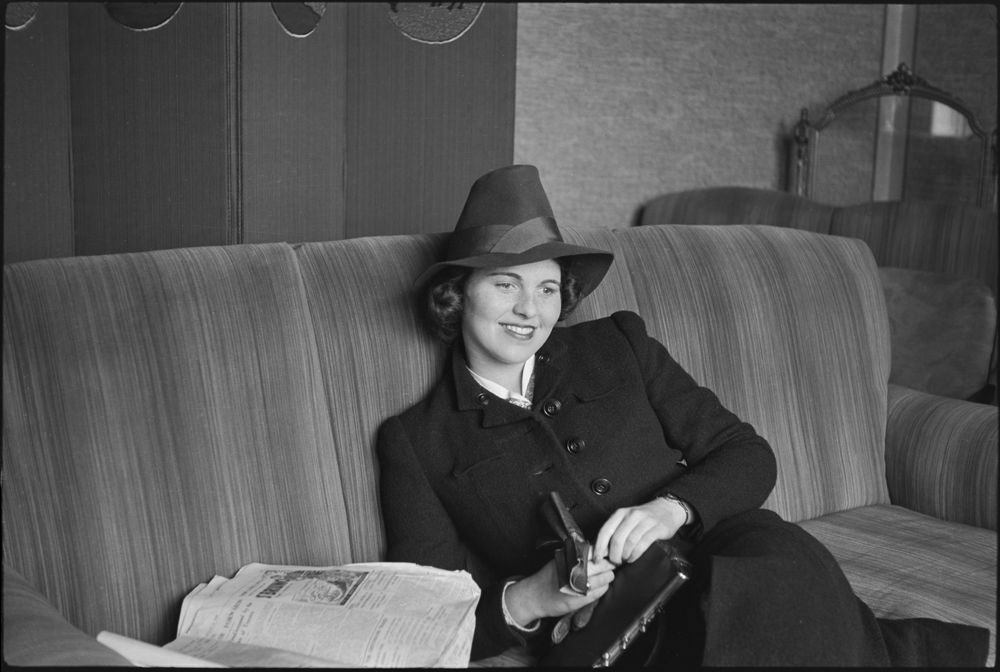

Following a lobotomy, Freeman observed various symptoms that he claimed showed that the surgery was successful: increased appetite, weight gain, positive affect and expression, general compliance and friendliness. Freeman also often photographed his patients prior to and following the procedure and added descriptions in order to provide “evidence” for the surgery’s success. One of his patients, “Case 121” (find pre- and post-surgery pictures here) has been described to have a hostile demeanor prior to receiving a lobotomy. In the photos following the procedure, the patient is reported to giggle a lot, and a picture of the patient a few years after the procedure shows that she is a full-time employee and is able to make independent decisions about her life. Another documented report of Freeman’s lobotomies is a patient labeled “Case 490” (find pre- and post-surgery pictures here) who was a patient with chronic severe pain and respiratory issues. The lobotomy alleviated the patient’s discomfort, however he passed away one month later from his illness. In this way, lobotomy has been used as a palliative procedure, with its primary purpose being to relieve symptoms of distress.

Into the Darkness

A well-known case of a lobotomy going wrong was that of Rosemary Kennedy, the sister of former U.S. President John F. Kennedy. When Kennedy was 23 years old, her father arranged for her to undergo a lobotomy for her delinquent and irritable behavior. The surgery, performed by Dr. Freeman himself in 1941 and during the early experimentation stages, left Kennedy incapacitated and completely unable to talk or walk. The failed operation resulted in her being institutionalized for the rest of her life in a mental health facility. While she was able to regain her ability to walk, she was never fully able to recover her independence and cognitive functioning until her passing in 2005 at age 86. Furthermore, her existence was concealed from her family by her father for many decades in order to hide the negative impact that the lobotomy has had on her. This particular case especially highlights just how multifaceted the negative impact of lobotomies may be, influencing not only the person’s cognition and physical ability but also various other aspects of their life such as their family relationships, career and wellbeing. Despite the disastrous outcome of Rosemary’s lobotomy, Freeman was able to continue performing the procedure on many more patients to come.

(Source: Rosemary Kennedy, The Eldest Kennedy Daughter)

Lobotomy was not only performed on patients with mental health issues. In the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published in 1952 during the reign of lobotomies in neuropsychology, homosexuality was placed under the category of mental disorders and was considered abnormal. It was, therefore, allowed for neurosurgeons to operate on homosexual people regardless of any proof that they had an actual mental health disorder, thus enabling surgeons (who, very often, also did not have a surgical license) to treat what only they thought was disordered. While on the topic of sexuality, it is crucial to mention that women with alleged disorders of sexuality were also frequent targets of lobotomy, these “disorders” primarily being outward appearance (e.g. heavy makeup, revealing clothes) and non-monogamous sexuality. Additionally, many women who were considered troublesome, like in the case of Rosemary Kennedy earlier, were also operated on in hopes that their obedience would be restored. Once again, this highlights that the scope of people who qualified for the surgery spanned far more than only those with mental disorders.

Despite its popularity and continued advertisement to the general population, doubt and skepticism toward the surgery continued to rise in tandem.

The Controversy

A notable and substantial reason for criticism was the low success rate and high mortality rate of lobotomies, observed with the most accuracy from Freeman’s work alone. Furthermore, the ethics of it all are heavily brought into question as nineteen of Walter Freeman’s patients were under the age of 18, one patient being only four years old at the time of their surgery and therefore unable to give consent. Not much is known about the pre-surgery procedure and whether details and informed consent forms were provided to patients, which is another point of concern regarding ethics.

In a lecture about the history of lobotomies, Miriam Posner stated that it is ”strange” how affect and expression served as key medical evidence during the lobotomy’s prime. In the first half of the 20th century, proper post-tests were not yet developed and one of the few post-surgical treatments was a document with aftercare instructions for the patient (document: Home Care Following Leukotomy). This means that there was never a way to properly assess the true impact and usefulness that lobotomy had on patients aside from taking photographs and documenting general affect and state of being. The surgery itself was very invasive and any failed attempt permanently damaged the brain beyond repair. At the time, brain scans such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) did not exist, implying that there was also no way to observe exactly how and where the brain was damaged if the surgery went wrong. As every human brain has slight structural and, sometimes, functional differences, a lack of proper orientation to detail for such a delicate organ additionally contributed to the vast differences in terms of the procedure’s outcome and side effects.

Perhaps the most intriguing point of criticism regarding the lobotomy and, especially, Freeman’s views on it is that its primary purpose seemed to be less about the alleged reduction of mental health impairments, but more about “fixing” people in order to make them into individuals who fit the societal standards of what “normal” behavior looks like. This was, as Posner described in her lecture, particularly evident when it came to his female patients who constituted the majority of Freeman’s lobotomy patients, with an estimated 75% by 1942. A patient of his who was a black woman was described, word-for-word, in her post-surgery file as going from a “dangerous person to a friendly helper.” Overall, Freeman’s views on gender and racial equality were the foreground in practically all stages of his work as a surgeon, from deciding whether a patient would get a lobotomy in the first place to assessing their health and state post-surgery. This further contributes to the ever-growing pool of evidence as to why lobotomies were unreliable, bias-driven and worthy of people’s wariness.

The Fall of Lobotomies

As the most prominent figure in the history of lobotomy, Freeman performed his last lobotomy in 1967, which ended catastrophically with his patient dying from a brain hemorrhage. He continued to believe in the benefits of the surgical procedure until his death in 1972.

The “official” large-scale fall of lobotomies began following the emergence of Chlorpromazine (marketed as Thorazine) in the mid-1950s, which was an antipsychotic drug used for the treatment of disorders like bipolar disorder and schizophrenia due to its mood regulating effects. Thorazine, as well as the medication developed afterwards, promptly replaced lobotomy and became the primary method of clinical treatment for patients with mental disorders. Although the surgery was never officially banned in any rulebooks nor the American Psychiatric Association (APA), it was mostly discontinued by the late 1970s due to ethical and moral discrepancies. Today, however, a more well-researched psychosurgery is still seldom used in cases where no other treatment proves to be successful. Furthermore, recent advancements in brain scanning techniques such as fMRI and TMS have been making the localization of brain damage and subsequent non-invasive treatment possible. The improper treatment of patients during lobotomy’s prime and the transition to non-invasive options contributed to the development of detailed ethical guidelines regarding consent, the rights of clinical patients and research subjects, and rules for the proper conduct of clinicians and researchers alike.

Educated (Personal) Review

Based on the argument portraying lobotomy as having a gendered and racial belief basis, a question arises - has lobotomy ever been aimed at actually improving people’s lives, or has its only purpose been to create individuals who are obedient followers of societal norms? Judging by Freeman’s views and him using images and the general external state of his patients as the only indicators of lobotomy’s success (or failure), it is worth mentioning that the surgery’s implications could indeed be much darker than they seem.

In a world where people are driven by success and motivated to be “perfect” individuals who can operate almost mechanically to meet life’s demands, procedures like the lobotomy were easily justified as a quick fix. This, in general, highlights the complexity of human societal norms, including the preference for able-bodied people, gender hierarchies, racial discrimination and classism, among others. This is not to say that treatment for mental health disorders is not valid - such treatment is beneficial and important. Lobotomy is, however, a prime example of how not to treat patients, where clinicians’ negative beliefs can be translated into devastating outcomes for those who do not align with said beliefs.

In essence, lobotomies were not just a medical treatment, but a way to surgically silence people’s visible suffering while permanently altering their functioning for the rest of their lives.

Author: Nika Murganic

References

Drescher, J. (2015, December 4). Out of DSM: Depathologizing homosexuality. Behavioral sciences (Basel, Switzerland). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4695779/

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (2025, July 11). Lobotomy. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/lobotomy

Freeman, S. (2023, August 18). How Lobotomies Work. HowStuffWorks Science. https://science.howstuffworks.com/life/inside-the-mind/human-brain/lobotomy.htm

Garnett, C. (2019, October 31). When Faces Made the Case for Lobotomy. National Institutes of Health. https://nihrecord.nih.gov/2019/11/01/when-faces-made-case-lobotomy

Kaye, H. (2023, April 25). The dark history of gay men, Lobotomies and Walter Jackson Freeman II. Attitude. https://www.attitude.co.uk/culture/sexuality/the-dark-gay-history-of-lobotomies-and-walter-jackson-freeman-ii-419069/

Lewis, M. (2024, September 26). From lobotomy to TMS: Transforming mental health treatments. Southern Live Oak Wellness. https://southernliveoakwellness.com/lobotomy-to-tms-how-science-evolved-to-treat-mental-health-ethically/

Mehta, S. S., Vadali, S., Singh, J., Sadana, S. K., & Singh, A. (2024, October 21). The Legacy of Egas Moniz: Triumphs and Controversies in Medical Innovation. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11578627/

Posner, M. (2010, November 13). Walter Freeman’s photographic forebears. Miriam Posners Blog. https://miriamposner.com/blog/walter-freemans-photographic-forebears/

Rodrigues, K. (2023, November 24). In a psychiatric hospital in São Paulo, women were the preferred target of Lobotomies. Casa de Oswaldo Cruz. https://coc.fiocruz.br/todas-as-noticias/in-a-psychiatric-hospital-in-sao-paulo-women-were-the-preferred-target-of-lobotomies/

Rosemary Kennedy | JFK library. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. (n.d.). https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/the-kennedy-family/rosemary-kennedy

Stone, J. L. (2001, March). Dr. Gottlieb Burckhardt--the pioneer of psychosurgery. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11446267/

Terrier, L.-M., Lévêque, M., & Amelot, A. (2019, September 10). Brain lobotomy: A historical and moral dilemma with no alternative?. World Neurosurgery. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1878875019324222

Tone, A., & Koziol, M. (2018, May 22). (F)ailing women in psychiatry: Lessons from a painful past. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5962395/

Source banner picture: The Quest for a Psychiatric Cure - The New York Times

Additional Sources for Your Interest

Dr. Miriam Posner Lecture: James Cassedy History of Medicine Lecture - Mind-Body Problems: Lobotomy, Science, and the Digital Humanities

Lobotomy Procedure Detailed (Video Contains Graphic Scenes): Prefrontal Lobotomy in the Treatment of Mental Disorders (GWU, 1942)

Rosemary Kennedy Timeline: Rosemary Kennedy from 0 to 86 years old Shutter Island Movie Review: Shutter Island; twisting and turning your mind